By MICHAEL BARBARO and STEVE EDERMAY 9, 2015

MIAMI — One day in the State Capitol in Tallahassee, Marco Rubio, the young speaker of the House, strayed from the legislative proceedings to single out a lanky, silver-haired man seated in the balcony: a billionaire auto dealer named Norman Braman.

This man, Mr. Rubio said in effusive remarks in 2008, was no ordinary billionaire, hoarding his cash or using it to pursue selfish passions.

“He’s used it,” Mr. Rubio said, “to enrich the lives of so many people whose names you will never know.” As it turned out, one of the people enriched was Mr. Rubio himself.

As Mr. Rubio has ascended in the ranks of Republican politics, Mr. Braman has emerged as a remarkable and unique patron. He has bankrolled Mr. Rubio’s campaigns. He has financed Mr. Rubio’s legislative agenda. And, at the same time, he has subsidized Mr. Rubio’s personal finances, as the rising politician and his wife grappled with heavy debt and big swings in their income.

Now, with Mr. Rubio vaulting ahead of much of the Republican presidential field, Mr. Braman is poised to play an even larger part and become Mr. Rubio’s single biggest campaign donor, with an expected outlay of approximately $10 million for the senator’s pursuit of the White House.

A detailed review of their relationship shows that Mr. Braman, 82, has left few corners of Mr. Rubio’s world untouched. He hired Mr. Rubio, then a Senate candidate, as a lawyer; employed his wife to advise the Braman family’s philanthropic foundation; helped cover the cost of Mr. Rubio’s salary as an instructor at a Miami college; and gave Mr. Rubio access to his private plane.

The money has flowed both ways. Mr. Rubio has steered taxpayer funds to Mr. Braman’s favored causes, successfully pushing for an $80 million state grant to finance a genomics center at a private university and securing $5 million for cancer research at a Miami institute for which Mr. Braman is a major donor.

Even in an era dominated by super-wealthy donors, Mr. Braman stands out, given how integral he has been not only to Mr. Rubio’s political aspirations but also to his personal finances.

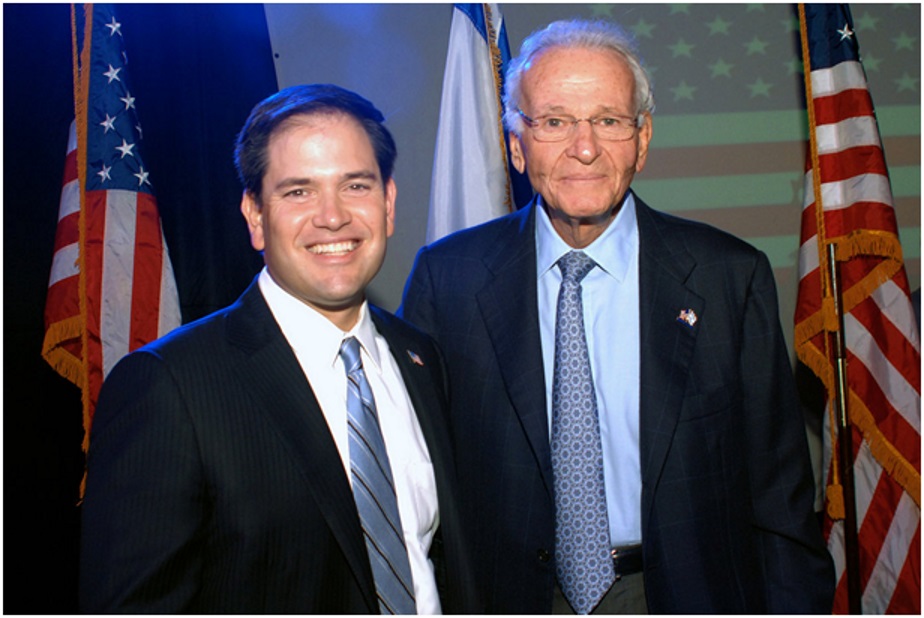

Credit

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Mr. Rubio, 43, is unabashed in acknowledging the influence of Mr. Braman, a commanding and litigious figure with so much clout in Miami that he almost single-handedly recalled a sitting mayor.

In an interview, Mr. Rubio described Mr. Braman as a father figure who had given him advice on everything from what books to read to how to manage a staff. After Mr. Rubio’s father died in 2010, Mr. Braman called every other day to check in.

Pressed on his financial ties to Mr. Braman, Mr. Rubio said in an interview that he saw no ethical issue. “What is the conflict?” he asked. “I don’t ever recall Norman Braman ever asking for anything for himself.”

He acknowledged that Mr. Braman had approached him about state aid for projects, such as funding for cancer research, but said that he had supported the proposals on their merits.

The reliance on Mr. Braman is likely to put a spotlight on the finances of Mr. Rubio, who ranks among the least-wealthy candidates in the emerging Republican field. Mr. Rubio left the Florida House of Representatives in 2008 with a net worth of $8,351, multiple mortgages and $115,000 in student debt. In his latest financial disclosure form, for 2013, he reported at least $450,000 in liabilities, including two mortgages and a line of credit.

Mr. Braman and aides to Mr. Rubio have declined to say how much personal financial assistance he has provided to Mr. Rubio and his wife, directly or indirectly, but it appears to total in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In a series of interviews at his office in downtown Miami, above showrooms of shiny BMWs and Rolls-Royces (he also sells Cadillacs, Audis and Bugattis), Mr. Braman praised the Rubios. He recounted what he described as “excellent service from them” over the years, and said he wanted nothing in return for his financial help.

“I’m not going to be an ambassador or anything like that,” he said.

Mr. Braman — a former owner of the Philadelphia Eagles; the chairman of Art Basel, which stages art shows; and a collector who owns works by Andy Warhol, Alexander Calder and Picasso — emphasized that there were limits to the friendship.

What Marco Rubio Would Need to Do to Win

“I also have a yacht,” Mr. Braman said, “that Senator Rubio has never seen.”

Mr. Braman has the manner of a man accustomed to getting what he wants, a trait that has endeared him to many in Miami as he battles against public subsidies for sports stadiums and ugly skyscrapers.

He was vacationing in France one summer when the mayor of Miami — not the one he had recalled from office — informed him that he would seek to raise taxes. Mr. Braman hung up the phone, turned to his wife and declared: “Goodbye, I’m heading back to Miami to fight this.” He returned home and led a successful campaign to block the increase.

“If you’re going to do something, you do it all the way,” he said.

As early as 2008, Mr. Braman made a bold prediction, captured in a video tribute to his friend: Mr. Rubio would be the first Hispanic president of the United States. Seeing that through in 2016, Mr. Braman said in one of the interviews, is “part of my legacy.”

The partnership began in the early 2000s when a Miami lawmaker introduced them. Mr. Braman, himself the son of immigrants, was instantly drawn to the story of Mr. Rubio, a child of struggling Cuban immigrants. By 2004, Mr. Braman and his wife had donated $1,000 to Mr. Rubio’s State House campaign, the first of many contributions.

Mr. Rubio quickly emerged as a dogged champion of Mr. Braman’s most cherished cause: state funding for a Miami cancer institute that bears the Braman family name.

Florida’s governor, Jeb Bush, had vetoed the funding in 2004, incurring Mr. Braman’s public fury. “Frankly, as a very active Republican, I’m ashamed of him,” Mr. Braman said then of Mr. Bush.

Mr. Rubio did not let it happen again. The next year, he secured the cancer funding over Mr. Bush’s objections. “Marco,” Mr. Bush wrote in a somewhat grudging email to a lobbyist at the time, “strongly wanted the Braman Cancer money.”

Soon, Mr. Rubio became a regular visitor to Mr. Braman’s office on Biscayne Boulevard. By the time Mr. Rubio was elected speaker of the House, the youngest in Florida’s history, Mr. Braman felt close enough to show up at the 2005 celebration in Tallahassee and deliver a memorable — and valuable — token of affection: a framed Revolutionary War-era American flag. It hung, on loan, in Mr. Rubio’s office for the entirety of his tenure as speaker.

In Mr. Braman, a Republican with a strong distaste for wasteful government spending, an ardent commitment to Israel and a seemingly limitless bank account, Mr. Rubio found a devoted sponsor.

When Mr. Rubio geared up for re-election to the House, more than a dozen individuals and companies linked to Mr. Braman, including his Honda and Cadillac dealerships, gave Mr. Rubio $500 each, the maximum donation allowed under Florida law.

When Mr. Rubio decided to write a book laying out a conservative vision for Florida’s future, Mr. Braman said, he chipped in money to pay for its publication.

When Mr. Rubio announced his signature legislative goal, an initiative to slash property taxes and raise the sales tax, Mr. Braman contributed $255,000 to the advocacy group lobbying for the changes, becoming by far its largest donor.

Mr. Rubio said the flow of donations from Mr. Braman had no effect on his decision-making as House speaker, adding that he would never give preferential treatment to a donor. But in 2008, when Mr. Braman sought the $80 million for the genomics institute at the University of Miami, a large taxpayer grant to a private college, Mr. Rubio delivered the opposite message: Mr. Braman’s request, he said, had tilted the scales.

Usually, Mr. Rubio said at a news conference at the time, he would have laughed off such an eye-popping pitch. “But when Norman Braman brings it to you,” Mr. Rubio said, “you take it seriously.”

Later that year, when Mr. Rubio left state government, determined to shore up his finances before running for the United States Senate, he landed a teaching job at Florida International University, agreeing to raise much of his salary through private donations.

Mr. Braman gave $100,000, according to records he shared with The New York Times. Dario Moreno, who oversaw the university center where Mr. Rubio worked and who taught classes with him, confirmed that Mr. Rubio had raised the money fro

In the spring of 2010, as Mr. Braman was donating heavily to Mr. Rubio’s Senate campaign, his company, Braman Management, hired Mr. Rubio as a lawyer for seven months. According to records provided by Mr. Braman, the company paid Mr. Rubio until a week before he was sworn in as a senator.

Four months after Mr. Rubio left the payroll, Mr. Braman hired Mr. Rubio’s wife, Jeanette, who had little professional experience in philanthropy, and her company, JDR Events, to advise the Braman foundation. Mr. Braman declined to discuss her compensation.

Mr. Rubio said the offers of work from Mr. Braman had a simple motivation: “We are close personal friends. They trust us.”

Mrs. Rubio’s job, fielding and vetting requests for donations to one of Miami’s biggest charitable foundations, has given her a major profile in the world of Florida philanthropy.

An internal Braman foundation document makes clear that Mrs. Rubio has become a crucial gatekeeper. “On hold,” read a notation next to a pending donation. “Wait to hear from Jeanette.”

At times, the foundation’s work has coincided with Mr. Rubio’s own globe-trotting political needs. In 2013, when Mr. Rubio traveled to the Middle East, Mrs. Rubio joined him, with the Braman foundation paying for her travel. According to Mr. Rubio’s aides, she was conducting work for the foundation abroad.

On four occasions, Mr. Rubio has traveled on Mr. Braman’s private plane, reimbursing him each time.

Mr. Braman acknowledged seeking the occasional “small favor” from Mr. Rubio’s Senate office. There was the daughter of the woman who does his nails, Mr. Braman recalled, who had an immigration problem, and the student from Tampa who wanted a shot at military school. In both cases, he said, Mr. Rubio’s staff was quick to respond. (Mr. Rubio’s staff said it had decided not to recommend the Tampa student.)

Mr. Braman seemed conflicted about his reputation as civic power broker, at once boasting of his ability to draw a high-ranking Miami official to his office with a single phone call and seeming anxious that he not be viewed as entitled.

“I don’t consider myself a fat cat,” he said. “Don’t make me out to be a fat cat.”

As he spoke in his office, an aide interrupted, presenting Mr. Braman with a yellow sticky note. The Florida Senate was about to vote on a bill he had sought, granting auto dealers like himself greater leverage over car manufacturers.

“That was fast,” Mr. Braman said.

Moments later, another adviser popped his head in, declaring victory. “Thirty to four,” he said of the vote, with a fist pump.